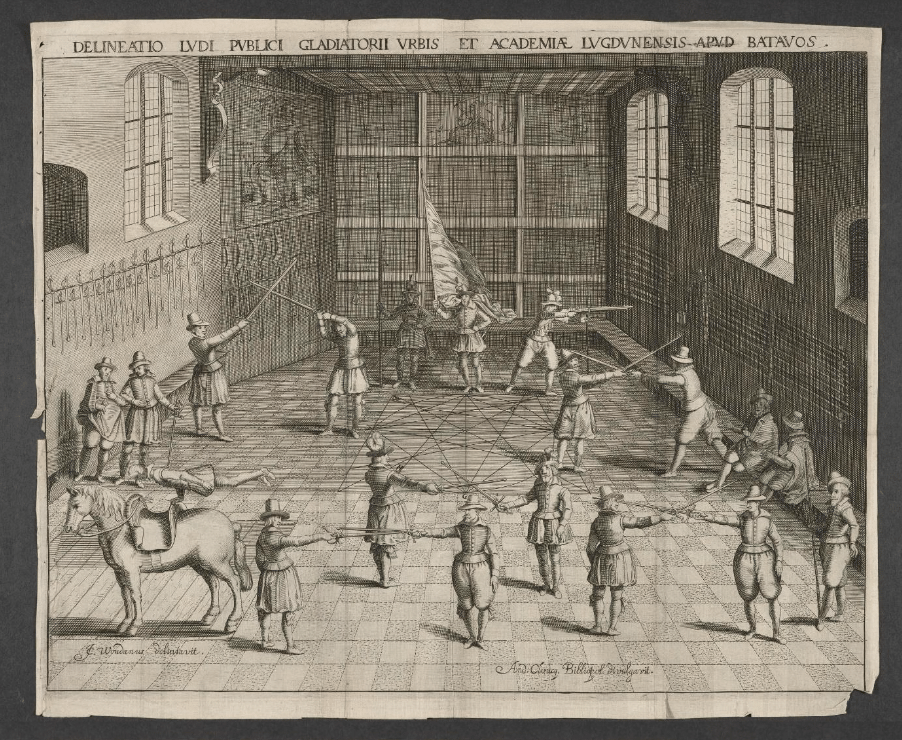

So what did a Shakespearean era fencing school look like? The short answer is, no one really knows, though perhaps a little like this one. This wonderful print, from an engraving by Jan Cornelius Woudanus, illustrates the fencing school at the University of Lieden in Holland in 1610. Although the fencing master was a well-known mathematician, the pattern on the floor was not for teaching geometry but a tool for learning footwork.

The weapons in the background are long swords (used with two hands), and a musket mounted on a pole. In the foreground are broadswords and rapiers, and in the racks on the wall, halberds and pikes. Clearly the artist is having a bit of fun for amongst the order and symmetry is a man doing a one-handed handstand on his horse and an unfortunate fencer with a sword through his head.

Apart from the sword-in-the-eye bit, it all looks very refined and gentlemanly. Whitefriars, however, being a rough and tumble part of London, wedged between Bridewell prison on one side and the Inner Temple Inns of Court on the other, would have served a broad cross-section of the community that was not quite so genteel.

Whatever the clientele, any place where men gather with a whole lot of swords and various other weapons, needs a set of rules, and the rules need to be vigorously enforced. Hence the sign in the fictional Whitefriars puts the rules prominently on display.

“NO SUSPECT PERSONS. (MURDERERS THIEVES DRUNKARDS QUARRELERS)”

The sign comes from a description of an actual sign at a London fencing school. Don’t you love how the fencing master felt the need to specify what comprises a ‘suspect person’? I suspect drunkards and quarrelers are fairly easy to spot, but how they could tell the murderers and thieves apart from the honest fencers is anybody’s guess.

The fencers at Lieden appear to be very well-dressed for the sweaty business of sword fighting but what did swordsmen wear when they were training? Workout wear wasn’t invented yet, and gone were the days of chainmail and armour. It would seem most men wore their usual attire of breeches and doublet, but perhaps not their best or fanciest outfit, for even a blunted weapon can tear or damage clothing. In the heat of summer the fencers might have stripped down to a linen undershirt but this would involve a trade-off between a need for some protective layers and potential over-heating. Modern fencing instructors wear padded vests or very thick leathers when offering up their body as a target, a practise which is most likely not a modern invention at all. Curiously, in the Lieden engraving the fencers are all wearing hats. I suspect this is more for a bit of head protection than for decorum or fashion just as I suspect any self-respecting English swordsman would scoff at the notion of wearing a hat while he is fighting, which other illustrations from the period would bear out.

Much of our knowledge about the English fencing masters comes from a document with the very unexciting title, Sloane manuscript 2530. The manuscript is a partial record of the Masters of Defence training and promotion system and provides a fascinating glimpse into the past. It lists participants in the various London Prize fights, the rank being sought, and the weapons they fought with. Listed among the ranks of Master is one John Evans of Whitefriars, who is now immortalised as the swordmaster in The Swordmaster’s Daughter, along with the location of his fencing school.

Originally Whitefriars was a Carmelite monastery and the monks (or friars) wore white habits, hence the name white friars. When Henry VIII established the Church of England all the monasteries were shut down in 1538 and largely demolished. Most of the buildings at Whitefriars were destroyed and built over but the old refectory building, or dining hall, remained and would have been the perfect location for a Fencing Academy, firstly because it would have been fairly large, similar in size to a nobleman’s Great Hall or a modern day school gymnasium. Fencing classes and training need a fair amount of space, especially if there are a few bouts and lessons going on at the same time.

The large refectory windows were an added advantage for fencing, good lighting being rather helpful when someone is thrusting the pointy end of a rapier in your direction. The refectory would also have had a large kitchen attached, as well as cloisters which could easily have been converted to living quarters and storage areas. Weapons were expensive, valuable, and a potential armoury for a would-be-rebellion, so being able to store them in a secure place was vital. A Master Swordsman living on site was a powerful deterrent for thievery and added another element of security.

In the early seventeenth century when The Sisters of the Sword series is set, Whitefriars would have been a bustling district. With Fleet Street to the north and its own Thames landing on the south side, it was only a few minutes’ walk to London’s two main thoroughfares. Sadly all that remains of Whitefriars today is a 14th century crypt believed to be part of the priory mansion and used as a coal cellar.

The ruins were discovered in 1895 and restored in 1920, and then again in 1991 during building work. They can be viewed through a glass window from Magpie Alley, off Fleet street. It might look like a few old stones and ruins but if you close your eyes and listen you might just hear an echo from Shakespeare’s time, a clash of blades, a call of en guarde and the tolling of the bells of the Old Saint Paul’s.

© 2022 All rights reserved

Made with ❤ in Australia